The greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) is a large bird entirely dependent on vast tracts of intact and healthy sagebrush habitats. The sage grouse is considered an “umbrella species,” because protecting sufficient sagebrush habitat to sustain the grouse also provides habitat for 350 other natives species of plants and wildlife that inhabit the Sagebrush Sea. Male sage-grouse are most recognizable by the spectacular dance they perform in the spring to court mates. Males have remarkable tail feathers that fan and yellow air sacs on their chests that puff out, to produce unique “plopping” sounds. The video above shows a male sage-grouse courting a mate on a site known as a “lek.” Females are less showy but their health is critically important for the reproduction and survival of the species. Sage grouse are closely tied to individual leks and nesting habitats, returing to the same sites to breed and nest year after year.

Once numbering in the millions in the Western sagebrush sea, greater sage-grouse have significantly declined from historic numbers estimated at 16 million birds to less than 500,000 today. The precipitous decline of sage-grouse is symptomatic of several factors all converging to make the sagebrush biome the most threatened landscape in North America. Public lands ranching, oil & gas drilling, climate change, fire, cheatgrass, and expanding energy development are among the chief threats to the species.

Western Watersheds Project has been advocating for greater sage-grouse to receive the protection of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) since 2004. Our 2007 lawsuit challenging the failure by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to protect sage grouse under the Endangered Species Act won a ruling that the listing process had been tainted by political meddling, establishing WWP as a nationwide leader in sage grouse conservation. In response, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife issued a new “warranted by precluded” finding that the grouse deserved the protections of ESA listing, adding it to the Candidate Species list.

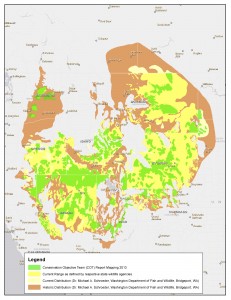

Under pressure from a sage grouser listing deadline set for September of 2015, the federal land management agencies, the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service convened a blue-ribbon panel of sage grouse experts called the National Technical Team, which in 2011 issued science-based recommendations on what protections the grouse need in priority habitats to survive and recover. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service then convened a Conservation Objectives Team to designate Priority Areas for Conservation. These two reports provided a sound basis for West-wide sage grouse conservation, and Western Watersheds Project and our allies pushed for strong, science-based sage grouse habitat protections as an alternative to listing the species under the Endangered Species Act.

The federal land-use agencies then undertook a West-wide planning process to demonstrate a sufficient commitment to protecting sage-grouse that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service would determine that existing regulatory mechanisms are adequate, and that ESA listing wasn’t necessary. WWP commented on all of the subregional plans released during this process, and WWP found pervasive inadequacies in all of them. WWP’s comments centered on our area of expertise: the direct and indirect harms to sage-grouse caused by public lands livestock grazing. The agencies turn a blind eye to the widespread degradation cows and sheep are causing in sage-grouse habitat, instead focusing efforts to conserve habitat on more fencing and livestock improvements, seeding, and vegetation “treatments” like sagebrush manipulation, prescribed burns, and juniper removal that are certain to further fragment sage-grouse habitat. To assess grazing, the agencies uniformly rely on determinations of rangeland health (BLM) or monitoring data (USFS). But, as WWP has learned and demonstrated repeatedly, the BLM’s standards in particular are ineffective measures of livestock impacts and fail to capture the real problems with grazing, even when they are actually conducted! And much of the time, the agencies claim not to have the funding to fulfill their monitoring promises.

Unfortunately, the planning process went off the rails amid political pressure from anti-conservation state governments and commercial industries that had a profit motive in avoiding sage grouse protections, and the new plans fall far short of that goal. In 2015, the plans were completed, riddled with loopholes, scientifically invalid protection levels, and priority habitats gerrymandered to leave the most vulnerable of the important grouse habitats unprotected. Declaring premature victory, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared the grouse “not warranted” for listing (although populations had continued to decline from 2010 when they were found “warranted”).

Importantly, all of the plans relied on site-specific grazing permit renewal processes to implement any changes in livestock management, rather than incorporating specific, measurable objectives into the plan amendments themselves. But none of the plans admitted that grazing permit renewals are most often rubberstamped under Congressional riders that exempt them from review before renewal. It could realistically be decades before any on-the-ground measures from these plans are implemented.

WWP once again led efforts to challenge the 2015 sage grouse plans in court, represented – together with our allies – by Advocates for the West. Our lawsuit sought to keep the existing levels of habitat protections in place, while compelling federal agencies to strengthen plan protections to scientifically-supported levels. Meanwhile, because Congress had blocked ESA listing for the sage grouse, the incoming Trump administration was able to undertake a gutting of what remained of the science-based habitat protections for sage grouse, without the consequence of incurring an ESA listing. WWP was able to draw the Trump plan amendments into our larger sage grouse plan case, and in 2019 Judge Winmill issued an injunction blocking the Trump plan amendments and reinstating the previously-existing protections.